Eywa & Brahman: Decoding Avatar Hindu Connections in James Cameron’s Cinematic Universe

नासतो विद्यते भावो नाभावो विद्यते सतः।

उभयोरपि दृष्टोऽन्तस्त्वनयोस्तत्त्वदर्शिभिः॥nāsato vidyate bhāvo nābhāvo vidyate sataḥ |

ubhayorapi dṛṣṭo’ntastvanayostattvadarśibhiḥ ||“The unreal has no existence, and the real never ceases to be. The truth about both has been realized by the seers of ultimate reality.”

— Bhagavad Gita 2.16

When James Cameron’s Avatar captivated global audiences in 2009, few recognized the profound Avatar Hindu connections woven throughout its narrative fabric. The fictional world of Pandora, with its interconnected consciousness and reverence for all life, mirrors foundational concepts from Vedic philosophy that have existed for millennia. As we examine the Avatar movie spiritual themes across the franchise—including The Way of Water and the Fire and Ash—we discover striking parallels between Eywa, the guiding consciousness of Pandora, and Brahman (ब्रह्मन्), the ultimate reality described in Hindu scriptures.

This exploration of Hindu roots in film reveals how James Cameron Avatar has inadvertently—or perhaps deliberately—channeled ancient Vedic wisdom into modern cinema. By decoding these Avatar Hindu connections, we can appreciate both the timeless relevance of Hindu philosophy and the depth Cameron brings to Pandora spiritual beliefs.

The Concept of Brahman and Its Cinematic Echo in Eywa![Avatar Hindu connections]()

The Brahman Avatar meaning extends far beyond the English word “soul” or “spirit.” In Vedantic philosophy, Brahman represents the supreme, unchanging reality that pervades all existence. The Chandogya Upanishad (3.14.1) declares:

सर्वं खल्विदं ब्रह्म

sarvaṃ khalvidaṃ brahma

“All this is indeed Brahman”

This non-dualistic understanding—that consciousness permeates everything—forms the bedrock of Advaita Vedanta philosophy. Brahman isn’t a distant deity but the fundamental substrate of reality itself, the consciousness that unifies all beings and phenomena.

When we observe Eywa Hindu connections in Avatar, we encounter remarkably similar concepts. Eywa functions as an omnipresent consciousness linking all living beings on Pandora through the neural networks of flora and fauna. The Na’vi people don’t worship Eywa as an external god but experience direct communion through their neural queues, achieving what Vedic texts call brahma-jñāna (ब्रह्म-ज्ञान)—knowledge of the ultimate reality.

The Avatar Hindu connections become particularly evident when Jake Sully describes his first experience with the Tree of Souls. His awe mirrors what the Katha Upanishad (2.2.15) describes as the realization of Brahman: a state where individual consciousness merges with universal consciousness. This concept of interconnected existence isn’t mere philosophy in Hindu tradition—it’s experiential reality accessible through meditation and spiritual practice, just as the Na’vi experience Eywa directly through physical connection.

Hindu philosophy in Avatar manifests most clearly in how Pandora spiritual beliefs reject the subject-object duality prevalent in Western thought. The Na’vi don’t see themselves as separate from nature but as integral threads in Eywa’s cosmic fabric. This mirrors the Vedantic teaching of tat tvam asi (तत् त्वम् असि)—”you are that”—which asserts the essential unity between individual consciousness (ātman) and universal consciousness (Brahman).

The Sacred Network: Indra’s Net and Pandora’s Neural Connections![]()

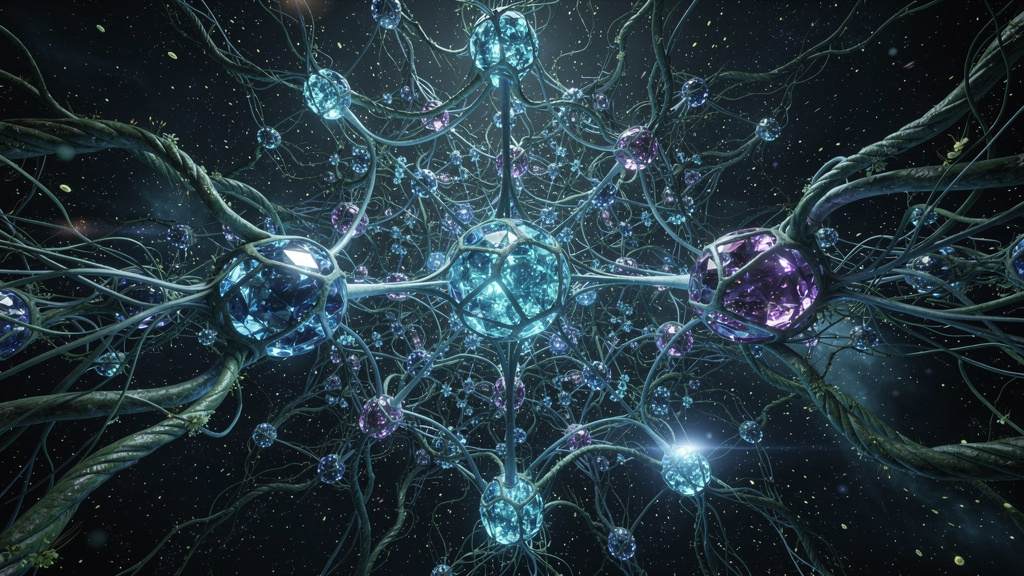

The visual representation of interconnectedness in James Cameron Avatar finds stunning parallels in the ancient concept of Indra’s Net (इन्द्रजाल), described in the Avatamsaka Sutra and referenced in Hindu texts. Imagine an infinite net extending in all directions, with a multifaceted jewel at each intersection. Each jewel reflects all other jewels, creating an endless cascade of reflections where everything contains everything else.

Pandora’s biological neural network—connecting trees, animals, and the Na’vi—operates on this precise principle. When Neytiri explains that “all energy is only borrowed,” she articulates the Hindu concept of samsāra (संसार), the continuous flow and exchange of energy and consciousness throughout existence. The Avatar movie spiritual themes emphasize that nothing truly dies; rather, energy transforms and returns to Eywa, just as Hindu scriptures teach that the ātman (आत्मन्)—individual consciousness—merges back into Brahman.

The Tree of Souls serves as Pandora’s equivalent to the cosmic axis mundi found across dharmic traditions. In Hindu cosmology, the kalpavṛkṣa (कल्पवृक्ष)—the wish-fulfilling tree—represents the connection between earthly and divine realms. Similarly, the aśvattha tree (अश्वत्थ), referenced in Bhagavad Gita 15.1-3, symbolizes the eternal, inverted tree of existence with roots in Brahman and branches spreading throughout material reality.

Avatar Hindu connections deepen when we examine how the Na’vi transfer consciousness through Eywa. This mirrors the Vedic understanding of consciousness as indestructible and transferable. The Bhagavad Gita (2.22) states:

वासांसि जीर्णानि यथा विहाय

नवानि गृह्णाति नरोऽपराणि।

तथा शरीराणि विहाय जीर्णा-

न्यन्यानि संयाति नवानि देही॥vāsāmsi jīrnāni yathā vihāya

navāni gṛhnāti naro’parāni |

tathā śarīrāni vihāya jīrnā-

nyanyāni samyāti navāni dehī ||“Just as a person sheds worn-out garments and wears new ones, likewise, the embodied soul casts off worn-out bodies and enters new ones.”

When Grace Augustine’s consciousness transfers to her Na’vi avatar through Eywa’s intervention, we witness a cinematic representation of this ancient teaching about consciousness transcending physical form.

Dharma and Duty: Jake Sully’s Hero’s Journey Through Vedic Lens

The character arc of Jake Sully embodies the concept of dharma (धर्म)—righteous duty aligned with cosmic order. Initially, Jake approaches Pandora as a mercenary, motivated by personal gain and loyalty to human corporate interests. However, his transformation reflects the journey from adharma (अधर्म)—actions misaligned with universal truth—toward dharma.

Hindu philosophy in Avatar presents Jake’s moral evolution as parallel to Arjuna’s crisis in the Bhagavad Gita. Like Arjuna, Jake faces conflicting duties: loyalty to his own species versus allegiance to truth and righteousness. When he ultimately chooses to defend Pandora against human exploitation, he embodies the Gita’s teaching that true dharma transcends narrow self-interest and tribal loyalty.

The concept of svadharma (स्वधर्म)—one’s unique duty based on nature and circumstances—manifests powerfully in Avatar Hindu connections. Jake discovers his svadharma isn’t serving corporate greed but protecting Eywa’s creation. This aligns with Krishna’s counsel in Bhagavad Gita 3.35:

श्रेयान्स्वधर्मो विगुणः परधर्मात्स्वनुष्ठितात्।

स्वधर्मे निधनं श्रेयः परधर्मो भयावहः॥śreyānsvadharmo viguṇaḥ paradharmātsvanuṣṭhitāt |

svadharme nidhanaṃ śreyaḥ paradharmo bhayāvahaḥ ||“It is better to perform one’s own duty imperfectly than to perform another’s duty perfectly. Even death in performing one’s own duty brings blessedness; another’s duty is fraught with danger.”

Avatar movie spiritual themes consistently emphasize that true strength comes from alignment with natural law—with dharma—rather than technological superiority or military might. The Na’vi victory over technologically advanced humans demonstrates the Vedic principle that dharma ultimately prevails over adharma, regardless of apparent power imbalances.

The Way of Water: Fluidity and the Vedic Understanding of Existence

![]()

Avatar: The Way of Water introduced audiences to the Metkayina clan and their ocean-based culture, deepening Avatar Hindu connections through water symbolism central to Vedic thought. Water (jala, जल) represents not just physical substance but consciousness itself in Hindu cosmology. The Taittiriya Upanishad identifies water as one of the pañca mahābhūta (पञ्च महाभूत)—five great elements—from which all creation emerges.

The Metkayina’s reverence for ocean life and their understanding of water’s spiritual dimension mirrors teachings from the Rig Veda, where water appears as both physical and metaphysical reality. The phrase āpo devīḥ (आपो देवीः)—”waters are divine”—from Rig Veda 7.49.4 reflects this dual nature. Water sustains physical life while symbolizing the flow of consciousness and spiritual purification.

James Cameron Avatar uses the ocean environment to explore fluidity as a philosophical principle. Hindu philosophy teaches anitya (अनित्य)—impermanence—as fundamental to material existence. Just as ocean currents constantly shift and reshape, all phenomenal reality remains in flux. Only Brahman, the unchanging consciousness underlying all change, remains eternal. The Metkayina’s adaptation to oceanic life demonstrates acceptance of constant change while maintaining connection to Eywa, the unchanging consciousness.

Avatar Way of Water Hindu connections extend to the concept of prāṇa (प्राण)—life force or vital energy. The Metkayina learn to hold breath for extended periods, mastering prāṇāyāma (प्राणायाम)—breath control—a fundamental yogic practice. This isn’t merely physical training but spiritual discipline, acknowledging that breath carries consciousness and connects individual beings to universal life force.

The tulkun, intelligent whale-like creatures in The Way of Water, embody the Vedic principle of ahiṃsā (अहिंसा)—non-violence. Despite their size and strength, tulkun choose peace, reflecting the highest dharmic ideal. Their persecution by humans for economic gain parallels countless teachings warning against lobha (लोभ)—greed—as a fundamental destructive force. The Bhagavad Gita 16.21 identifies desire, anger, and greed as the “three gates to self-destruction.”

Reincarnation and Consciousness Transfer: From Vedic Wisdom to Pandoran Reality

One of the most profound Avatar Hindu connections involves the transfer of consciousness—what Western audiences might call “reincarnation.” The Na’vi ritual that permanently transfers Jake’s consciousness from his human body to his avatar body cinematically represents the Vedic understanding of consciousness as independent from physical form.

Hindu scriptures extensively discuss punarjanma (पुनर्जन्म)—rebirth—as the soul’s journey through multiple bodies. The Brahman Avatar meaning includes understanding that while bodies perish, consciousness (ātman) remains eternal and indestructible. The Bhagavad Gita 2.20 declares:

न जायते म्रियते वा कदाचि-

न्नायं भूत्वा भविता वा न भूयः।

अजो नित्यः शाश्वतोऽयं पुराणो

न हन्यते हन्यमाने शरीरे॥na jāyate mriyate vā kadāci-

nnāyaṃ bhūtvā bhavitā vā na bhūyaḥ |

ajo nityaḥ śāśvato’yaṃ purāṇo

na hanyate hanyamāne śarīre ||“The soul is never born nor dies; having come into being once, it never ceases to be. It is unborn, eternal, permanent, and primeval. It is not slain when the body is slain.”

Jake’s consciousness transfer through Eywa mirrors this principle perfectly. His awareness, memories, and identity—his ātman—move from one physical vessel to another, facilitated by the universal consciousness (Eywa/Brahman). This isn’t science fiction fantasy but a cinematic interpretation of ancient Vedic metaphysics.

Hindu philosophy in Avatar extends beyond individual reincarnation to collective consciousness. When the Na’vi connect with ancestors through the Tree of Souls, they access smṛti (स्मृति)—collective memory—stored in Eywa’s network. This parallels the concept of ākāśa (आकाश)—cosmic space or ether—which in Vedic cosmology functions as the repository of all knowledge and experience. The Akashic Records, referenced in Hindu and yogic traditions, suggest that all events, thoughts, and experiences remain permanently encoded in cosmic consciousness.

Environmental Harmony: From Aranyakas to Pandora’s Ecosystems

The environmental consciousness displayed by the Na’vi reflects principles found in the Aranyakas (आरण्यक)—”forest texts”—portions of the Vedas composed by sages dwelling in forests. These texts emphasize harmony between human society and natural ecosystems, viewing forests not as resources to exploit but as sacred spaces embodying divine presence.

Pandora spiritual beliefs mirror the Hindu concept of vana-devatā (वन-देवता)—forest deities—acknowledging consciousness and divinity within nature itself. Trees, rivers, mountains, and animals aren’t merely material objects but manifestations of divine consciousness. The Rig Veda addresses prayers to plants, waters, and earth as conscious entities worthy of respect and reverence.

Avatar Hindu connections become particularly relevant in our current ecological crisis. The destruction humans bring to Pandora in pursuit of unobtanium mirrors real-world exploitation of natural resources. Hindu philosophy offers the concept of loka-saṃgraha (लोक-संग्रह)—welfare of the world—as the highest motivation for action. The Bhagavad Gita 3.20 states that wise individuals should work for loka-saṃgraha, ensuring their actions benefit collective wellbeing rather than narrow self-interest.

James Cameron Avatar presents the Na’vi practice of asking forgiveness before taking life—even hunting for food—as central to their spirituality. This directly parallels Hindu and Vedic practices where prayers and mantras accompany any taking of life, acknowledging the consciousness within all beings. The principle of minimum necessary harm guides ethical behavior, recognizing that all life participates in the same universal consciousness.

The Tree of Souls functions as Pandora’s equivalent to sacred groves found throughout Hindu tradition. Sacred groves—protected forest areas associated with deities—have preserved biodiversity for millennia in India. The ecological wisdom embedded in such religious practices demonstrates that Avatar movie spiritual themes aren’t merely fictional ideals but practical applications of ancient environmental ethics.

The Conflict Between Materialism and Spirituality: Maya and Delusion

![]()

The human antagonists in James Cameron Avatar embody fundamental concepts from Hindu philosophy: māyā (माया)—illusion—and avidyā (अविद्या)—ignorance. Corporate executives and military leaders see Pandora purely as material resource, blind to its spiritual dimension. This represents māyā—the illusion that material reality is all that exists, that consciousness arises from matter rather than matter arising from consciousness.

Colonel Quaritch and Parker Selfridge exemplify beings trapped in avidyā—ignorance of ultimate reality. They pursue wealth and power, driven by kāma (काम)—desire—and lobha—greed—unable to perceive the deeper truth that Eywa represents. The Bhagavad Gita 16.13-15 describes such individuals:

इदमद्य मया लब्धमिमं प्राप्स्ये मनोरथम्।

इदमस्तीदमपि मे भविष्यति पुनर्धनम्॥idamadya mayā labdhamimaṃ prāpsye manoratham |

idamastīdamapi me bhaviṣyati punardhanam ||“Today I have acquired this; I shall fulfill this desire. This wealth is mine; that wealth too shall be mine in future.”

This mentality—endless acquisition, viewing everything as property to possess—creates the central conflict in Avatar Hindu connections. The Na’vi, aligned with Brahman through Eywa, recognize the futility of such pursuits. They understand what the Mundaka Upanishad teaches: lasting fulfillment comes from spiritual realization, not material accumulation.

Hindu roots in film like Avatar reveal timeless wisdom: technology without spiritual awareness leads to destruction. The humans possess superior weapons and machines, yet they lack viveka (विवेक)—discrimination between real and unreal, permanent and temporary. The Na’vi, though technologically primitive, possess profound spiritual wisdom making them evolutionarily advanced in consciousness.

Yoga and Unity: Tsaheylu as Physical Manifestation of Spiritual Union![Tsaheylu]()

The neural connection the Na’vi call tsaheylu—”the bond”—serves as a physical metaphor for what Vedic philosophy describes as yoga (योग). The root yuj means “to yoke” or “to unite,” and yoga fundamentally represents union between individual consciousness and universal consciousness.

When Na’vi connect their neural queues to animals, trees, or each other, they experience direct union—literal yoga. This isn’t symbolic or metaphorical in Pandoran reality but actual merging of consciousness. Similarly, Hindu philosophy in Avatar demonstrates that yoga aims for samādhi (समाधि)—complete absorption where boundaries between self and other dissolve.

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali describe eight limbs of yoga culminating in samādhi. The Na’vi practice all eight limbs organically:

- Yama (यम) and Niyama (नियम): Ethical disciplines reflected in their respect for all life

- Āsana (आसन): Physical mastery demonstrated by their agility and strength

- Prāṇāyāma (प्राणायाम): Breath control, especially among Metkayina

- Pratyāhāra (प्रत्याहार): Withdrawal from external distractions during connection with Eywa

- Dhāraṇā (धारणा): Concentration practiced in hunting and rituals

- Dhyāna (ध्यान): Meditation during communion with Tree of Souls

- Samādhi (समाधि): Complete union achieved through tsaheylu

Avatar Way of Water Hindu connections expand this yogic dimension through the Metkayina’s emphasis on breath, heartbeat, and mental stillness. Tsireya teaches Jake’s children to slow their heartbeat and calm their minds—classic prāṇāyāma and meditation techniques. The ability to bond with ilu and skimwing requires yogic mastery—stilling mental chatter to achieve unity with another being’s consciousness.

The mating bond between Na’vi partners represents prema (प्रेम)—divine love—expressed through permanent tsaheylu connection. This mirrors the Vedantic teaching that ultimate reality is sat-cit-ānanda (सत्-चित्-आनन्द)—existence, consciousness, bliss. True love unites beings at the level of consciousness, transcending physical attraction or emotional attachment.

The Feminine Divine: Eywa and Shakti

![]()

Eywa’s feminine presence in Pandora spiritual beliefs parallels the concept of Śakti (शक्ति)—the divine feminine principle in Hindu philosophy. Śakti represents creative power, the dynamic force through which Brahman manifests the universe. While Brahman remains unchanging consciousness, Śakti is the active principle bringing forth creation, preservation, and transformation.

Hindu scriptures, particularly Shākta texts, describe the universe as the body of the Goddess—Devī (देवी). Everything that exists is Her manifestation, Her play (līlā, लीला). Similarly, all of Pandora exists within and as Eywa. The distinction between creator and creation dissolves, revealing non-dual reality.

The Devī Mahātmya, a sacred text celebrating the Divine Mother, declares:

या देवी सर्वभूतेषु चेतनेत्यभिधीयते।

नमस्तस्यै नमस्तस्यै नमस्तस्यै नमो नमः॥yā devī sarvabhūteṣu cetanetyabhidhīyate |

namastasyai namastasyai namastasyai namo namaḥ ||“To the Goddess who resides in all beings as consciousness, salutations to Her, salutations to Her, salutations to Her again and again.”

This perfectly describes Eywa’s nature—consciousness dwelling in all beings. The Avatar movie spiritual themes consistently portray Eywa not as external deity but as the consciousness pervading all life, protecting and balancing the ecosystem.

The Na’vi relationship with Eywa also reflects bhakti (भक्ति)—devotional love. While Vedantic philosophy emphasizes knowledge (jñāna, ज्ञान) of non-dual reality, bhakti traditions honor the personal dimension of divine consciousness. The Na’vi express profound devotion through songs, rituals, and prayers to Eywa, while simultaneously experiencing direct union through tsaheylu. This balances the paths of jñāna-yoga and bhakti-yoga, showing they aren’t contradictory but complementary.

Cyclical Time and Eternal Return: Fire and Ash

As the Avatar franchise progresses toward Fire and Ash, we anticipate deeper exploration of destruction and renewal—core themes in Hindu cosmology. Hindu philosophy understands time as cyclical rather than linear, moving through vast epochs called yugas (युग). The universe undergoes endless cycles of creation (sṛṣṭi, सृष्टि), preservation (sthiti, स्थिति), and dissolution (pralaya, प्रलय).

The Brahman Avatar meaning encompasses this eternal cycle. While Brahman remains changeless, its manifestations continuously arise and dissolve like waves on the ocean. The Bhagavad Gita 8.19 states:

भूतग्रामः स एवायं भूत्वा भूत्वा प्रलीयते।

रात्र्यागमेऽवशः पार्थ प्रभवत्यहरागमे॥bhūtagrāmaḥ sa evāyaṃ bhūtvā bhūtvā pralīyate |

rātryāgame’vaśaḥ pārtha prabhavatyaharāgame ||“The multitude of beings come into existence again and again. They are dissolved at the coming of night, O Arjuna, and manifest at the coming of day.”

Fire holds dual symbolism in Vedic thought. Agni (अग्नि)—fire—both destroys and purifies, transforming one state into another. Fire burns away impurities (doṣa, दोष), allowing renewal and rebirth. The Fire and Ash likely explores how Pandora—and Eywa—respond to catastrophic destruction, demonstrating the Hindu principle that destruction and creation are inseparable.

James Cameron Avatar has consistently shown that Eywa maintains balance through cycles of death and rebirth. Individual organisms die, but their energy returns to Eywa, redistributed throughout the ecosystem. This mirrors the concept of karma (कर्म)—action and consequence—as the mechanism by which cosmic balance maintains itself across time. Every action creates effects that ripple through the interconnected web of existence, eventually returning to their source transformed.

Hindu roots in film like the Avatar series remind modern audiences of ancient wisdom: nothing truly ends; everything transforms. Ash fertilizes soil for new growth. Destruction clears space for creation. The eternal dance of Shiva (Naṭarāja, नटराज)—cosmic dancer who simultaneously creates, preserves, and destroys the universe—may find its Pandoran expression in future films.

Practical Lessons: Applying Vedic Wisdom from Avatar to Contemporary Life

The Avatar Hindu connections offer more than philosophical comparison—they provide practical guidance for contemporary challenges. As we face ecological crisis, social fragmentation, and spiritual emptiness, the wisdom embodied in Pandora spiritual beliefs becomes increasingly relevant.

Interconnectedness in Daily Life: The Vedic principle that all beings share fundamental unity suggests treating others—human and non-human—with respect and compassion. When we recognize that harming others ultimately harms ourselves within the web of interconnected existence, ethical behavior becomes natural rather than imposed obligation.

Environmental Stewardship: The Na’vi model of expressing gratitude for resources received and taking only what is necessary offers practical application of ahimsā—non-violence—and santoṣa (संतोष)—contentment. Rather than endless consumption, we can adopt minimalist approaches, honoring the consciousness within all beings and maintaining reverence for the natural world that sustains us. This practice cultivates awareness of our interdependence with nature and encourages sustainable living aligned with ecological balance.

Spiritual Practice: Hindu philosophy in Avatar demonstrates that spiritual realization requires practice, not merely intellectual understanding. Just as Na’vi children learn to bond with animals through patient practice, we can develop meditation, prānāyāma, and mindfulness practices that deepen our connection with universal consciousness.

Community and Service: The collective nature of Na’vi society, where individual welfare intertwines with communal wellbeing, reflects loka-samgraha—working for the welfare of all. Modern individualism often creates isolation and suffering. Recognizing our fundamental interconnection motivates service to others as service to our expanded self.

Presence and Awareness: The Avatar Way of Water Hindu principle of “seeing” (oel ngati kameie—”I see you”) calls for genuine presence and awareness in relationship. This mirrors the Vedic practice of sākṣī-bhāva (साक्षी-भाव)—witness consciousness—where we fully perceive others without judgment or projection, honoring their essential being.

Balance and Harmony: Eywa constantly maintains ecological balance, neither allowing one species to dominate nor permitting disruption of natural cycles. Similarly, Vedic philosophy teaches madhya-mārga (मध्य-मार्ग)—the middle path—avoiding extremes and maintaining balance in diet, work, relationships, and spiritual practice. The Bhagavad Gita 6.16-17 emphasizes that yoga succeeds through moderation in all activities.

Conclusion: The Eternal Relevance of Avatar Hindu Connections

As we’ve explored throughout this analysis, Avatar Hindu connections run far deeper than superficial similarities. James Cameron Avatar has created a cinematic universe that—whether intentionally or intuitively—channels core principles of Hindu philosophy into accessible narrative form. The Brahman Avatar meaning, the concept of interconnected consciousness, the cyclical nature of existence, and the balance between material and spiritual dimensions all find powerful expression in Pandora spiritual beliefs.

Avatar movie spiritual themes resonate globally because they tap into universal truths that Vedic sages recognized millennia ago. The Fire and Ash promises to deepen Hindu philosophy in Avatar by exploring destruction and renewal, continuing the franchise’s meditation on eternal principles. Avatar Way of Water Hindu connections expanded our understanding of consciousness through oceanic symbolism, and future installments will undoubtedly reveal additional layers of spiritual wisdom.

The Hindu roots in film exemplified by the Avatar series demonstrate that ancient dharmic teachings remain profoundly relevant for addressing contemporary challenges. Environmental destruction, social fragmentation, and spiritual crisis all stem from forgetting our fundamental interconnection—the truth that Eywa represents cinematically and Brahman represents philosophically. These Avatar Hindu connections invite us not merely to appreciate cinematic artistry but to integrate timeless wisdom into daily living.

By recognizing these parallels, we honor both James Cameron’s creative vision and the eternal wisdom of Vedic tradition. We discover that Eywa and Brahman are ultimately two names for the same reality: the conscious unity underlying all existence, the sacred ground of being that connects every life form in an infinite web of relationship and meaning.

Author’s Note

This exploration of Avatar Hindu connections springs from two deep personal interests: my love for James Cameron’s visionary cinema and my independent study of Sanatan Dharma. The parallels between Eywa and Brahman, Pandora’s interconnected consciousness and Vedic philosophy, emerged through multiple viewings of the Avatar films enriched by my understanding of Hindu scriptures.

These observations represent my personal interpretation and experiential understanding. I offer this perspective as one enthusiast’s journey, hoping to deepen appreciation for both Avatar’s spiritual dimensions and the timeless wisdom of Vedic tradition.

While I have watched Avatar: Fire and Ash, I have intentionally limited references to avoid spoilers for readers. A deeper exploration of the Hindu philosophical themes in Fire and Ash may be covered in future writings if there is interest.

ॐ तत् सत्

Om tat sat

(Om, That is Truth)

Comments are closed.